We understand our lives as stories.

All art is a story which humanity tells itself, and narrative is the underlying structure of that endeavor. It is an accounting of events in an intentional fashion or order. Art comes out of the imaginative construction of the story. Our perception of the world—from vision to hearing and so forth—is the process of filtering unwanted stimuli (or directing active attention to desired affects information). Changing the filters is creativity. Re-telling the same old stories but in new ways continues the dialog that builds and evolves culture.

When Louis Henry Gates, Jr. (American literary critic, born 1950) said that "people arrive at an understanding of themselves in the world through narratives" he was saying that narrative is the foundation for the creation of culture, and the backbone of the civilizing process. Roland Barthes (French literary critic and philosopher, 1915-1980) echoed this when he wrote "Narrative is present in every age, in every place, in every society; it begins with the very history of mankind and there nowhere is nor has been a group of people without narrative. All classes, all human groups have their narrative, enjoyment of which is very often shared by men with different opposing cultural backgrounds. Caring nothing for the division between good and bad literature, narrative is international, trans-historical, trans-cultural; it is simply there, like life itself."

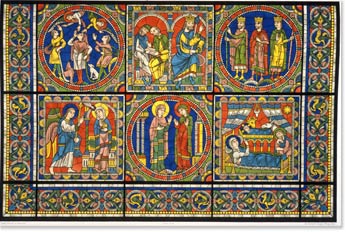

Engraving, after stained glass in Chartres Cathedral depicting scenes from the life of Jesus Christ (central figure in Christianity, circa 2 BCE -36 CE).

The creative use of metafora gives the inflection that allows us to transcend the simple telling of events one after the other. Storytelling allows us to move into new realms of interpretation and stimulation of the imagination that defy the pat conventions of chronology. E. M. Forster (British novelist, 1879-1970) defines story as "a narrative of events, arranged in their time sequence." Each new teller or artist brings to the underlying narrative new translations and meaning and each new audience receives this act of creativity in new ways, carrying it forward as it is meaningful and useful in new forms to yet newer audiences. Thus, the myths which underlie our culture evolve over time, as our quest for understanding continually moves forward. The fineness of the story or myth whether told in word, movement or image, is in the creative use of metafora, or the inventions of new forms of it.

Time itself is the story, a sequence into which we put the narrative of our passing through space. We construct a beginning, a middle and an end to events that we relate to give shape to our lives. Paul Ricoeur (French philosopher, 1913-2005) states that narrative is inseparable from temporality. He takes temporality to be the structure of existence that "...reaches language in narrativity and narrativity to be the language structure that has temporality as its ultimate reference."

Despite the fact that time moves forward, we seem to need closure in narrative. Each audience brings its own sense of an end to its engagement of the story or the creative idea whether it is finished in the formal sense or not. The spectator or reader carries the experience with them opening it and closing it as their own imagination engages and re-engages the experience. In one sense, there is no definitive closure to the stories that society tells itself with narrative, as we are constantly dreaming it forward. The only finality that an individual can really know is death; otherwise our narrative is the legacy we leave by being creative.

The new interactivity of the Realm of the Circuit adds further dimension to the issue of closure, the narrative and the story. If in more conventional narratives, there was a beginning, middle and end, in cyberspace everything is to be continued. The viewer or operative can disrupt, re-configure the meter of the poetry, edit the film, and transform the music to his or her own ends. We live in a remix culture where one person's creative output becomes the fodder for a generation with the access to digital tools and the inclination to re-tell old stories from their own perspective. Once the audience can perform these gestures, the so-called closure made by the author is in a state of flux. The new technologies bring us back in a way to the early form of story telling, that of sitting in a circle, listening to the griot and taking away from that experience one's own adaption for a new cultural legacy.

Can a narrative acted upon by those who receive it in cyberspace, and who in turn become authors, ever stop evolving? Absolutely not: it is inherent in our very nature, in the creative license we individually have, the thoughtfulness of our interactions that we produce culture, evolving the narrative into new metafora where a new kind of temporality occurs. The internet has become the modern griot.