Michelangelo (Italian artist and designer, 1475-1564) believed the process of sculpture was that of freeing the form (the final sculpture) from the unfinished rock. The difference between a rock (raw, unformed material) and a sculpture is the intention of the artist, the use of the rock as a metaphor to convey an idea or feeling.

Objects have the potential to create a permanent record, whereas movement endures only in the memory of those who observe it. Likewise, sound endures only so long as it is being created, and there is someone to hear it. This profound notion, posed by George Berkeley (Irish philosopher, 1685-1753) in the eighteenth century, takes on new meaning when one considers the digital encoding of any creative act. Does the virtual world need a physical trace to exist?

We know that the digital file that encodes sound can be burned onto a compact disc, encoded onto a portable MP3 player, or even written in longhand as zeros and ones on a sheet of paper. Yet, these objects are only "carriers" for the encoded act. They are not the originals. In contrast, the spiritual importance of the Shroud of Turin depends on the fact that it is thought to be the original cloth that wrapped the body of Jesus Christ. Representations and copies can be made, but they are not equal to the original. Likewise, sound can be recorded either in analog form (as an old-style vinyl album) or in digital form. Analog information is hard to duplicate, but digital information is not. This is why piracy of music is so widespread in the digital age.

to hear it,

Does it make a sound?

-attributed to George Berkeley (Irish philosopher, 1685-1753)

Much of what occurs in the computer is fleeting, in existence for no longer than a moment, changes in the voltage state of millions of microscopic switches. Computer-based creativity achieves permanence less as a traditional, stable object, than in its ability to transfer from one computer to another, much like a computer virus (think of the rapid spread and reach of the computer viruses). In Western culture, beginning with Giotto (Italian artist, c.1267-1337) in the thirteenth century, paintings were principally representations of other objects: The frame of the painting was the metaphoric window frame; the canvas represented the scene beyond. The object of the painting was meant to be a mirage, a simulation of the process of human vision, a record of an actual or historical event, or even an allegorical event, one that never happened. In the nineteenth century, photography took the burden of representation from painting: Painting needed to change to survive.

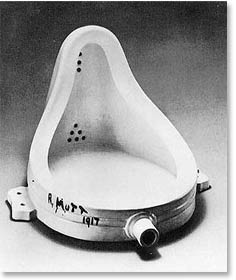

R.Mutt (Marcel Duchamp, French artist, 1887-1968), Fountain, 1917

At the turn of the twentieth century, modernist painters broke with the depiction of reality. They no longer painted representations of reality, but moved toward formalism and abstraction. Paint and brushstrokes in and of themselves became imbued with meaning, and the painting was no longer a metaphor for vision, a window to another world, but an object to be looked at. It became an exploration into our fantasies; the nature of paint and canvas became the substance of cultural icons.

Photography democratized representation by allowing anyone to make an image, and became a window to the world for practically everyone. Because the image was so easily duplicated, the photograph itself had little value as a unique object. Once an image is reproduced and disseminated to culture at large, it begins to take on iconographic meaning: representation of significant cultural values. Today, as objects, vintage photographs take on financial value.

the earth itself

- William Morris (British artist and writer, 1834-96)